This article explores Kierkegaard’s modes of existences through a sociological framework. By applying macro-historical analysis, the author attempts to trace how societal structure is corelated with the individual experience. As ideological thought in society reinforces the notion of social exclusion, the individual would experience different form of despair: the ethicist experience conscious despair and of lacking infinitude and possibility in modernity, the aesthete experience despair of ignorance and of lacking finitude and necessity in liquid modernity. Based on these premises, the author attempts to describe the sociological correlation between ideologies, social institution, and the individual existence in the society.

Keywords: Modernity, Liquid Modernity, Ethical Individual, Aesthete Individual, Existential Despair

Introduction

The objective of this paper is to explore the existential relation between the individual and society. The individual mode of existence is parallel with the societal mode of thought. And it is the aim of this article to describe the individual existential condition by tracing its effect from the collective experience of the society. In order to achieve this aim, the author employs a similar Kierkegaardian analysis towards modernity and liquid modernity by using various sociological terms to capture the external societal context and imputing existential terms to diagnose the internal existential condition of the individual.

Kierkegaard has criticized Hegel, chief of socio-historical analyst, for his objective systemisation on the society and yet have sacrificed the analysis of the human individual – a typical commentary of modern society (Kierkegaard, 2009: 161-165, 294-295; Paula in Stewart, 2011: 34). It may be concluded that the objective analysis has “dehumanized” the subject, and thus the accumulation of abstract knowledge does not have the qualitative capacity to transform the individual; it is the subjective – the personalisation of knowledge in a concrete existential sense, is a matter of relevance. However, by focusing the discursive spotlight on the individual, Kierkegaard was less concern to extend his existential reading into the collective crowd. If Kierkegaard claims that every individual should be detracted from the crowd and reflects subjectively for his own existence, then the author would like to argue that it is also important for the individual to know the crowd to distinguish the properties of the self and the society.

One implication of such premises is to personalise knowledge into the personal existence. As this paper applies an existential sociological analysis, the author attempts to analyse the relation between the two poles: the objective (ideology) and subjective (individual experience). It does not deny the classical tradition to describe the ontological existence of social facts but complements it by adding personalising effect on the individual experience (Tiryakian, 1965). Ideology is contingent with the individual modes of existences. Every type of society is governed by a certain form of knowledge, and the collective thought is not only cognitive in nature, but it is also relevant to the individual’s inner experience within a structural situation (Mannheim, 1936: 240, 261; Speier, 1985). It changes how one perceives the society, how one psychologically perceives oneself, and how one lives and act in accordance to the existential nature of his being. The personalisation of sociological knowledge, can be analised by imputing Kierkegaard’s existential categories “The Aesthete” and “The Ethical” to the individual’s socio-historical setting.

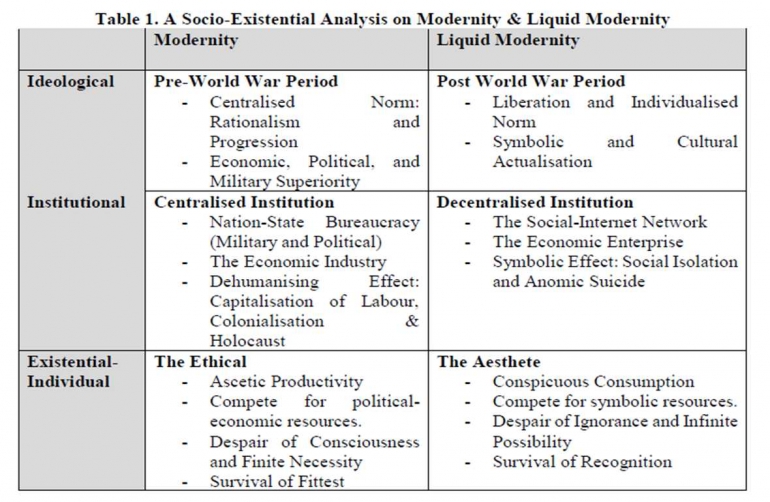

The author has selected a certain historical timeframe to see the shifting pendulum of ideological change in the Western hemisphere. The historical timeframe acts as a typological ideal-type to capture the Aesthete and Ethical existential state of the individual. The two modes of existences can be further understood by comparing individual mindset in the modern pre-World War period and liquid modern post-World War period. As each ideological-existential property has reached its peak, the society would experience inertia by using up its previous resources and finding a new form of resource (Botta, 2016). To the individual, one would experience “micro-inertia”, known as despair. Modernity utilises the resources of scientific-rationalism and productivity; liquid modernity utilises the resources of emotional-network and consumerism.

Furthermore, this paper proposes that the individual existential despair is parallel to ideologies. Social alienation is governed by constructed ideologies. The construction of “the ideal self”, its formula of would also inevitably exclude “the unwanted other”, thus reinforcing such discrimination through institutional structure within the society. The sense of alienation is not only a sociological one, but its practice is supported by various social institutions, rippling psychological waves into the existential person. Through the interrelated discussion of existentialism and sociology, the author suggests that we would be able to further comprehend the framework of ideologies, social institutions, and their correlation towards the individual’s structure of existence. Based on this presumption, the author would like to briefly discuss the two questions in this article: 1. How does modernity produces conscious despair in the ethical mode of existence? 2. How does liquid modernity produces ignorant despair in the aesthete mode of existence?

Methodology

This paper applies a macro-historical approach to describe the idiographic traits of society. The style of analysis is derived from the sociology of knowledge which employs the framing of an ideal-type to pinpoint the general perspective (Weltanschauungen) of a particular culture and epoch (Kettler, 1967). This ideological characteristic is later reflected from the observer’s point of view. The method of generalization is limited into a certain historical period. And later, the author continues to describe how the certain ideal-types (modernity or liquid modernity) are practised and maintained through various social institution. In this case, the author attempts to employ this method in the Western hemisphere: Modernity, ranging from the Industrial period of The Enlightment to the World War period; and Liquid Modernity ranging from the Post-World War period to the mass technological usage of social network. The author uses various literatures to support this description.

Furthermore, this paper also applies a method of subjective analysis to raise the issue: how certain socio-historical setting is relevant towards the individual’s mode of existence. Kierkegaard often proposes a dialectical reading of the abstract-objective issue through the method of double reflection to relate the objective (society) and subjective (individual) (Kierkegaard, 2009: 62-69). Sociological analysis is functioned capture the exterior relations between groups and individuals. In this article, the author would like to penetrate the description of the ideological and institutional component into the interior structure of individual’s existence, thus imputing the categorical terms: “The Ethical”, which is parallel to the communal norm in modern society; and “The Aesthete”, which is parallel to the individualised lifestyle in liquid society.

A Kierkegaardian conceptual framework on society

Kierkegaard’s philosophical thought is strongly influenced by two streams of tradition: the intellectual tradition of Hegelianism during his particular period of time, and the religious tradition of Lutheran Pietism. The Hegelian dialectics is originally used to explain world history in a philosophical system. However, Kierkegaard have made strong critic towards Hegel in the Concluding Unscientific Postscript for its totalising philosophical system in viewing human history, and yet omitted philosophical reflection of the individual.

Kierkegaard’s critic on Hegel can be traced to his religious upbringing whereby Lutheran Pietism has stressed the importance of the individual. Pietism is a religious tradition that challenges the objectified theological system, de-objectifies the dogmatic structure and allows emotional internalisation of values into the subject (Berger, 1967: 59; Weber, 1930: 81). It may be stated that Pietism has placed the individual faith as the sole focus of religious life, and that though this method, one would experience transcendence and have a clearer view on the object of analysis. Although Kierkegaard does not completely deny traditional orthodoxy, his neo-orthodox hermeunitic has allowed the “personalising effect” in reading both religious and non-religious discourses.

As Kierkegaard attempts to reformulate his own dialectic to describe the individual’s phases of existential life, he combines both Pietism and Hegelianism. His Lutheran reading on Hegel found that the individual would pass through three existential stages: The Aesthete begins with the consumeristic and unexamined repetitive lifestyle, continues with The Ethical who abandoned his previous stage and began making choices and commitments which conforms to the ideal communal norms, and at the end, the individual, very rarely perhaps, would reach the religious stage whereby the individual by religious faith would transcend the ethical norms of his society and have a personal encounter with The Eternal Thou. In some sense, Kierkegaard reversed Comte’s three stages of society, from the positivistic into the religious, in clarifying the individual mode of living.

The epistemological structure of Kierkegaardian thought can be categorised into two distinctive types: it is knowledge about something or self-knowledge. Kierkegaardian philosophy points towards the relationship between the society and the self. However, his philosophical thought has once again placed greater emphasis towards the individual. It may be argued that knowledge about “something” comprises of objective scientific knowledge of society and individual. Knowledge of society is not only external, but it has relevance towards the individual in an existential manner: social context produces individual experience. It is by this ground that the connection between sociology and existential philosophy can be achieved (Jakway, 1998). At the same time, Jackway argued that Kierkegaard’s philosophical writing can be associated with symbolic interactionism and Marxism. The former emphasises the individual’s accumulation of social consciousness in the social context, the latter emphasises the ideological critique towards the society.

The significance of ideology critique is located in the birth of existential despair. As ideologies signifies the norms of society and its standard of successful living, therefore the same ideologies also signify the standard of failed living. In other words, every individual is experiencing daily anxiety that existentially threaten anyone who do not conform towards the communal norms of the crowd. Social meaning is derived from ideologies, or cultural mentality, as Sorokin suggested has impact towards individual personality (Jeffries, 2005). By describing the experience of such anxiety in individual, we are able to capture to what extend that certain ideology is or not authentic for the individual and social existence. Ideologies tend to over-idealise itself and thus it is crucial for one to be an “existential Marxist” to observe and avoid the potential decline society, being temporarily detracted from unauthentic crowd. However, unlike Marx who focused on the social-political group relation, Kierkegaard invites individuals to reflect the on psychological effect of modernity (Paula in Stewart, 2011: 37). Through the instrumental lense of negavity (via negativa), one is able to detect the limits of socio-political project and its decline (Golomb, 1991: 71). It is as Westphal argues that there are no political theory or any established order that is self-sufficient. (Tilley in Stewart, 2015: 485).

Sociologically, this conceptual framework is aimed to provide a general critique towards ideologies by relating it with individual existential experience. The method of criticising ideologies is not limited to the macro-abstract dimension, but it should be related into micro-existential level. The effect of ideologies produces differing existential states. In this case, modernity produces the Ethical individual, liquid modernity produces the Aesthete individual. Social context is parallel to individual experience. Just as how the historical transition from modernity to liquid modernity (Pre-World War to Post-World War period) depicts socio-cultural standards for successful living, individual experience would also show different existential properties and existential despair (Westphal, 1996: 20-34).

The relevance of structure & social changes to the individual

In the previous section, the author has described about the sociological framework of Kierkegaard’s philosophical themes. In this section, the author attempts to survey previous literatures on societal structure and social changes as the ground (social context) to support existential analysis of the individual. In this article, social structure can be differentiated into three major components: ideological, institutional, and individual. Sociological analysis is mainly focused on the macro (structural) and meso (institutional) level of analysis. The structural level of analysis is comprised of the societal values which regulates the society on the normative plane. The institutional level of analysis is supported by various social institutions which makes concrete of the societal values into everyday practices. On the individual level of analysis, it discusses the relevance of ideology and institution into individuals’ psychological-experiential condition, also known as the existential analysis.

There are several sociological writings which have tackled much on the issue of knowledge and ideology. The most prominent sociologist whom have attempted to systematise such analysis is Karl Mannheim. Mannheim differentiated knowledge and ideologies. Knowledge is the totality of ideas which organises a certain society in geographical place and historical time; knowledge can also be understood as the “social matrix” which overtly governs the structure of collective and individual. It is the “Social Soul” or culture of the society. In contrast, ideologies are the particular ideas which various socio-political institutions propagates to govern the population according to the interest of certain elite group. According to Mannheim, knowledge is neutral, but ideology is utopic in nature; just as how socialism is the ideological apparatus to promote communism – a classless society, ideology is the means towards the utopian end. The differentiation of knowledge and ideology is important because Mannheim argues that major amount of the population is not conscious towards the ideas which governs them. By tracing of the source of idea, as Mannheim stated, would provide a more comprehensive picture of the normative dimension, and that the individual or whoever so was observing the society, would not fall into the interest of certain ideological propaganda as proposed by political elites. The epistemology by which Mannheim applies in his sociological method is echoing Descartes’s view on the object-subject relation. The sociology of knowledge is about the knowledge which permeates in the society-individual relation, and the sociologist reads the society by making conscious of one’s independent ontological position with the society: by realising how one’s knowledge and behavior is molded from the after-effect of the societal normative source. The continual reflection of knowledge within oneself and the society, it is implied, that the observer (sociologist) is able to trace and map the ripples of ideologies in the institutional apparatus and daily social lives (Mannheim, 1979).

The second sociologist whom have discussed on the similar issue of knowledge is Pitirim Sorokin. Sorokin, unlike Mannheim, did not placed emphasis on the nature of ideologies. He utilises the term “cultural mentality” to describe the “social soul” of society. Sorokin argues that a certain society is governed by a logic-meaningful unity in the structure of norms. These meaningful “nodes of norms” are spread throughout the society in the culture, arts, science, and daily social lives, and when “dots are connected” they provide a general pattern which governs societal lives. Sorokin provided the example that Ascetism and idealistic philosophy is connected to one another, likewise Materialism and Empirical philosophy belongs to each other, as both types of notion share common metaphysical similarities in their respective areas. The former provides the ground for the ethic of absolute principles and the latter provides the social atmosphere for the ethic of happiness (Sorokin, 1957). Through three components of society (cultural, society, and personality), knowledge when it is made actual into the daily lives become an ethic – the collective individuals’ personality and individualised norms of living in the social environment (Jeffries, 2005). And yet, much about the argument which Sorokin proposed is different from Mannheim. Mannheim argues about how knowledge governs the social structure, Sorokin argues that knowledge (cultural mentality) is malleable, and the change of cultural mentality determines the properties of social structure and social lives. Sorokin described two different poles of living: the sensate which orients towards materialism and the ideational which orients towards idealism. Sorokin finds the “invisible hand” or Pendulum of Social change which directs social changes. When a certain society exhausted all of its previous resources to reach the peak of its culture, it encounters the moment of inertia and take a new form of cultural mentality, thus social changes happen.

What is the most apparent social change that we have encountered in the latest socio-historical period? The author would cite Bauman’s work that the most imminent and appealing changes is the shift from the knowledge and culture of modernity to liquid modernity in the 20th and 21st century. The pendulum shift is mainly driven by institutions which touches the fabric of social and economic lives. Modernity has been predominantly occupied by hard power resources such political-economic progress, and liquid modernity is filled with soft power resources like symbolic-consumeristic lifestyle. During the European Enlightment whereby the Western’s economic-political growth is dominated by industrial activities, the individual work ethic and cultural mentality supports the normative ideology of reason and progress. However, as it has been stated in the previous section that ideologies tend to exclusive in its own norms, European political and economic progress has at the same time allows the spread of Westerrn Imperalism, Colonialisation, the militarisation of nations, and produces the rational-bureaucratic form of Holocaust. The Western cultural mentality of reason has not only exhausted its scientific-economic resources but has abused its materials to produce tragic calamities in human history. In return, the traumatic response of Western society towards the tragic of World Wars has otherwise countered the ideology of immoral-reasoning progress and move towards the ideology of blissful possibilities. Liquid modernity, in this sense, allows the room whereby individuals could no longer fear the growth of economy into a weapon of war, but utilise capitalism for consumerism, into a lavish lifestyle. The sudden liquification of social structure has been the second most drastic change in Western history: the first liquification is against the authoritarian Church-State, the second liquification is against the militaristic national state (Bauman, 2005).

The position of Existential-Sociological analysis is to observe how does social structure (Ideology and Institution) and social changes (Modernity and Liquid Modernity) is affected into the individual’s existential mode of living. Every mode of living is derived from social context and individual’s choices, it is the I and Me in Mead’s terms. The constructed individual (me) takes his social energy from the ideological and institutional apparatus, and at the same time, the free individual (I) take the stance in the social environment. The stance of the individual is existential, and the author would like to use Kierkegaardian analysis to describe the individual’s existential relation towards the notion of modernity and liquid modernity. The following table attempts to provide a plotted summary on the relation between social context and the individual’s existential relation:

Modernity is understood as mode of social life which emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, it is highly engaged in the growth of science and industry. Giddens have stated that modernity is the historical discontinuity from the religious institution in Western Europe; the French Revolution is a particular socio-historical event which marked the new episode of epoch. Pioneering sociological thinkers such as Durkheim, Marx and Weber had observed that modernity is a “social metamorphosis” from the confined state of traditional socio-religious lives. Modernity is the fertile soil whereby the growth of capitalism and nation-state is also eventually realised (Giddens, 1990).

Modernity is a Western project of positivistic rationalism and socio-political progression in a linear historical grand narrative (Bauman & Bordoni, 2014: 122). The former is modernity’s counter reaction towards religious institution, the latter is the utopian project during the Enlightment. The sequence is introduced in August Comte’s stages of societal life beginning with the religious stage, philosophical, and then towards material-positivism – It is a critique towards the State-Church institution and a movement for objective reasoning and the construction of non-religious moralism. In this ideological scenario, religion has lost its former grip in determining individuals’ lives. The normative value by which modernity has constructed promotes efficiency for the cause of socio-political progression. If rationalism produces science and objective-positivistic paradigm, it also emerges in social forms through institutional apparatus.

Ideological umbrella is pillared by social institutions. Unlike other sociological thinkers, Weber predicted that the main cause of modernity and its dehumanising effect is located in bureaucracy; it is not about social solidarity nor class struggle as proposed by Durkheim and Marx. Bureaucracy is the institutional incarnation of rationalism, it is the catalyst which converts modern ideology into concrete everyday situation. Rationalism is not only defined within the scope of exact sciences whereby the philosophy of positivism is the most popular paradigm at that time, but it is the societal expression in the pursuit of fixed and objective value in human civilisation. As rationalism and science detracts the human dependency on the religious institution, bureaucracy shifted the dependency on the nation-state. The state purposes the legitimate power of the legal coercion to centralise and organise various industrial and socio-economic activities (Weber, ed. 1978: 165, 314). On certain degree, Weber saw that bureaucracy serves as a legal and effective means to organise economic labour to fuel industrial capitalism. He had also extended his arguments in The Protestant Ethic by claiming that Calvinistic ascetic values have similar logical-meaningful connections which stimulates capitalism in Western Europe. Religion, the old tradition of Europe although is vanishing, retains certain characteristics which enhances the new tradition of modernity. This argument might as well perhaps be Weber’s presupposition that modernity allows whatever kind of values to exist as long as it is adhering to the mentality of progression, whether it is scientific or religious.

Nevertheless, there are unintended consequences in modernity. Weber saw that the notion of “putting chaos into order” through the existence of bureaucracy has depersonalising effect that turns into social exclusion. If scientific inquiry reduced human beings into intelligent materials, the fatalistic commando of bureaucracy has reduced human individuals into industrial soldiers, or rather, machines. The extreme application of bureaucracy is known as “Iron Cage” whereby the citizens of labour movement is fitted wholly for economic-political purposes, thus reaffirming and reproducing the stiffness of the established order (Kalberg, 2001). And yet modernity’s “will-to-order” did not end as a mere solid modernity, it is extended to achieve “triumphant modernity”. Once again, as the ideological foundation of modernity also consists of socio-political progression, it is not only bureaucracy that became the industrial motor within the European civilisation, but it also involves Western Imperalism to extract industrial materials from outside the European geopolitical territory. As knowledge of “order and progress” are the ideological blueprints of

European tower of Babel, thus capitalism and colonialisation are twin coexisting materials which supported asymmetrical power relation of “the capitalist and labourers” in Europe, “the Occidental and Orientals” outside Europe (Campbell et al, 2018). Here, not only bureaucracy is used in the political sphere, but hard military power was assumed just means to achieve the ends of an “ideal” European civilisation. Weber who assumed that Calvinism is a rational-religious tool for capitalism, it is also the same idea that unknowingly justified colonialisation under the name of capitalism, modernity and religion: Gold, Glory, and Gospel (Luttikhuis & Moses, 2012). It appeared that modernity’s promise to liberate individuals to pursue objective-rational morality, has eventually been seduced by the objectifying power of Order and Progression. The extreme progression of economic and political affirmation, in the name of rationalism, has eventually abandoned ethical compassion, and revealed such dehumanising society such as the Holocaust and World Wars (Bauman, 1989: 15; Cannon, 2016; Petersen, 2003).

As we now transit to the Kierkegaardian analysis of the modern individual, I would like to propose the knowledge of modern society leans towards the ethical mode of existence. The knowledge of modern individual that he or she is living in a linear progress requires work ethic to pursue that aim. The Ethicist is one who is conscious of self and communal norms, striving to dutifully conform towards the ethical rules of the society (Evans, 2004: 47). The general pattern of individual living in the modern epoch is marked by ascetic living as it is claimed to be the most rational and effective basis for bureaucratic efficiency and industrial productivity. The individual who works ascetically is the ethical person, and one who is consumeristic is unethical, for the ideological notion of order and progress requires individual commitment towards the crowd. Without putting the individual into such existential position, it would be difficult to reinforce the Established Order of modern society. It does not mean that there is no single position for the Aesthetic individual (the consumeristic one), however, the ideal-type, knowledge, or cultural mentality of modern Europe is more logical-meaningfully sound to the Ethicist in Kierkegaard’s terms: one who is conscious that he/she is part of the communal project, and conformation to its ethical demands is necessary.

And yet, the presupposition that ethical commitment is mandatory also puts the modern individual into some form of despair. The first form is the despair of consciousness, which illustrates the individual as being alienated from the ideal self, is the existential struggle in seventeenth century Europe. If there is a grand-narrative progress, then one has yet to finish the long road, and it can be observed through social relations. The asymmetrical power relation that established social institutions places the individual in a continuum: one who ascetically conforms to the ideological-institutional criteria is the “the elite”; and “redundant people/wasted human” who fails to conform – both kinds of individuals in the modern game suffers the problem of comparison (Bauman, 2005: 95). The ethical state demands comparison of ethic that the individual who misbehaves is less ethical. And the presupposition that some individuals are “more ethical” (more conforming to Rational Productivity) is existing, the logical consequence of such arguments could also “rationally” claim that “the other” is justifiable to be excluded.

Furthermore, the ethical mode of existence in modernity is also susceptible towards the despair of lacking possibility and infinitude. The knowledge of modernity presupposes Rationalism and Economic-Political progression, and yet it also “post-supposes” the reduction of human individual into objects. As it has been mentioned that bureaucratic fatalism of Iron Cage has dehumanised individuals into mere bureaucratic-capitalistic compartments, and there are no other alternatives whereby individuals could “survive” if they leave the modern arena as “disqualified participants”. Thus, being reduced into industrial machine has become the “only” necessary path (despair of lacking possibility), and yet it is also a reductionistic approach which undermines human individual’s capacity for creativity and meaningful living (despair of lacking infinitude) (Kierkegaard, 1980: 33-42). At the end, the despair of the Enlightment is located in the notion that the materialistic and positivistic nature of modern knowledge is tuned to view human individuals as robotic machines of capitalism, colonialism and militarism.

Liquid modernity and the aesthete’s despair

After the World War period, various philosophical reflection arises to answer the problem modernity. The question is no longer about modernity but against it: “If the modern project ends up in violent militarism, what is the alternative project that is available?” While some suggest that Postmodernity - the rejection of any fixed project is the utopian alternative, in reality Postmodernity is not fully exercised: the growth of industries and basic bureaucracy are still necessary to maintain progression in the midst of global socio-economic competition, in fact economic industries have evolved rapidly causing unprecedented economic growth in the West. The position of the current Western society is not fixed modernity nor anomic Postmodern, it does not fall into the either extremes but is positioned in between the spectrum. Bauman named this phenomenon as Liquid Modernity as it is the new mode of contemporary social life which suggest a “more flexible form of modernity”. The author tends to lean towards Bauman’s view on the current society as it is experiencing an atmosphere of “greater freedom (not total freedom)” in the globalised network society.

The apparent ideological worldview in the social mode of Liquid Modernity is Liberation and Consumerism. If modernity is born as a protest towards the State-Church, liquid modernity is a protest towards modernity. In each historical transition, there is a counter reaction towards the social structure whereby each stage claims that they ought to be liberated from the previous societal mode. In each stage, each mode suggests a certain form of project: If modernity puts rationalism and progression as its utopian destination, liquid modernity places individualised liberation and production of opportunities as its new primary objective (Bauman, 2000:62). In this post-industrial scenario, the political sphere no longer holds obligative demands upon the citizens, the economic sphere instead has the stronger role to comply towards the individuals’ needs.

The character of institutions has also evolved into a more “liquified state”. Unlike modernity, the liberating nature of social institutions has caused the privatisation of values; individuals are not made for institutions, but social institutions are now made for the individuals’. Security is no longer the obligatory objective aimed by institutions, they have been opened up towards the fulfillment of desire. Individuals no longer hold a communal interest for each person is “at one’s own centre of issue” (Gane, 2001). It is very likely that social institutions were adjusted to please and meet the desires of the consumers. Therefore, bureaucracy and economic industries that were known as iron cage “solids” and requires machine-like discipline violates the idea of individual liberation (Scaff, 1987). Those solid institutions have been replaced by liquid social institutions such as social network (internet) and economic enterprises (malls) which opens up the vast sea of choices and possibilities. Liquid modernity opens the room for the fertile growth of creative industries and innovative products and discoveries. And yet, the liberation that such modernity provides constitutes the consumptive society - the social atmosphere that consumers were continually seduced by concrete commodities and abstract signs to self-actualise, attain social status and affection (Braudillard, 2001; Hardt, 1999).

However, liquid modernity does not end in the liberation of individuals to consume signs attached to concrete enterprised goods. In this mode of social living, individuals have replaced the quality of social relation into quantities of networks and uncommitted relationships (Bauman, 2003). The ideological nature of liberation mutates further to the most abstract form of privatised institutions, namely social network (The Internet). Signs are not only narrowed to the purchase of commodities in the shopping malls, the human person is commodified into visual signs (digital personas), infinitely distributed and consumed across space and time in the internet. It is through this method whereby ordinary individuals surrender their inner private lives to be commodities of seduction in the strata of popularity. Through the use of social media, ordinary individuals reconstruct themselves into a digitalised self, imitating the celebrity persona, and also to add or delete the digital other in the process of consummption.

In the existential sense, the era of consumerism and seductive possibilities suggest the aesthete mode of existence (Gary, 2016). The aesthete is understood as one who has no self, ignorant of one’s authentic existence as one who depends on the consumption of external commodities to define the self. Liquid modernity has induced the knowledge that the individual is liberated to consume every possibility which satisfy the desire, and yet it is precisely in the uncontrolled production of infinite chances, that the self experience continual anxiety. The ethicist in this case experience the despair of ignorance that one does not have an independent self as the identity is continually shapeshifted by signs displayed by the economic enterprise and internet.

The despair which the liquid individual experience is lack of finitude and necessity. This form of despair shows that in the individual do not have a matured selfhood, one is fantasised and defined by signs (Evans, 2004: 45-46; Lazaratto, 2004). Signs are the symbolic status which the individual derives from what he or she consumes to signify social identity. If modernity produces robotic individuals, then liquid modernity produces liquid individuals. These individuals do not remain in a relatively fixed identity, one is constantly searching, and consuming external factors which define one’s identity. The individual will always be updated, decorated, and malleable with the unpredictable waves of trend. With the infinite possibilities continually produced by social institutions, the self lives in the fantastical realm of signs (Kierkegaard, 1980: 30-37, 42-47). However, it is precisely in this notion that the individual is in constant state of anxiety and restlessness as one could easily be left behind and disappear if he or she is incapable to appear in new signs.

Furthermore, as the person of immediacy lives in connection with infinite personas, one is in constant audition to imitate “the popular other”, and to please digital consumers – this is the logic of “follow and following. And yet because the individual is tangled in a huge network, the individual is perceived as “isolated dot” in the vast globalised network - ready to be overwritten by new trends, disappear from the scene of digital crowd. Thus, in liquid modernity although the Aesthete may emotionally feel the ecstasy of symbolic satisfaction, however if the mood is not maintained along the continual rise of seduction, the cold boredom and depression would arrive and brings the isolated individuals into suicide as a new form of “holocaust”: whereby fear and insensitivity and loneliness will become the end means of liquid modernity (Bauman & Donskis, 2013: 94-132). With the growing use of technological innovations, creative marketing (advertisements), and social medias, the current society contains such familiar knowledge of liberation and anxiety.

Man’s search for authenticity

As we return to Kierkegaard’s philosophical framework, we find that in each societal mode of knowledge, the individual lives in a mode of existence and is contingent to certain form despair. The difference in societal knowledge does not allow the individual to be completely free from the circle of despair. In the contrary, the movement from modernity to liquid modernity shows the “deconstruction of norms” and pulls the individual back from the Ethical to the Aesthete stage of existence. Although it is not valid that all society in the Western hemisphere is moving in the state of liquidity, nevertheless this trend shows that societal norms of progression in the Western region (Europe and America) is being reinterpreted or overwritten by consumptive lifestyle. It is quite interesting to note that as several societies tends to be “ethical” to achieve higher level of socio-economic welfare by conforming to the knowledge of progress, at the midpoint of the linear historical journey, those societies tend to move backward to the “aesthete” to enjoy the welfare it has accumulated.

Thus, the question for man’s existential authenticity is still a challenge to be debated, particularly as we are shifting back and forth in the pendulum of solid modernity and liquid modernity, between the Ethical and the Aesthete. Kierkegaard proposed that man’s authenticity is neither located in the Aesthete nor Ethical mode of existence nor the synthesis of both stages, but rather in his search in the authentic of I-Eternal Thou relation. This is not very different from Sorokin’s arguments that the Actual mentality also includes the role of religion as they are the most enduring form of knowledge that has been transmitted throughout history, providing the metaphysical and existential options for human existence.

Nevertheless, Kierkegaard proposed that readers should remain highly critical towards religion itself. Kierkegaard, although a Lutheran writer, spends most of his philosophical career criticising the Lutheran Church which he claims have prevented individuals from reaching authenticity (Religious stage), but remained in the form of ritualistic Christian practices (Ethical stage) at church and continues Borguiesse lifestyle at secular life (Aesthete stage) (Kierkegaard, 1968: 121-123). Kierkegaard’s critic towards the local religious institution of Denmark reminds us of how various social institution, secular or religious, tend to strain us into unauthentic identity. The author, echoes with Kierkegaard that the quest for authenticity still remains in this epoch.

Conclusion

This article attempts to describe the relation of knowledge and individual existence. The author has used the ideological, institutional, and existential level of analysis to compare the difference of Modernity and Liquid Modernity towards human experience. It is realised that modernity is associated with the ideological notion of rationalism and progress, institutional mechanism of bureaucracy and economic industry, existential characteristic of Ethical living. Liquid modernity is associated with the ideological notion of liberation and individualised norm, institutional mechanism of social network and economic enterprise, and the existential characteristic of Aesthete living. The quest for authenticity still remains a challenge as the cultural mentality of modernity and liquid modernity is insufficient to provide an existential satisfaction for the individual.

References

- Bauman, Zygmunt and Leonidas Donskis. 2013. Moral Blindness: The Loss of Sensitivity in Liquid Modernity. Polity Press.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 1989. Modernity and Holocaust. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Polity Press.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2003. Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds. Polity Press.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2005. Work, Consumerism, and the New Poor. Open University Press.

- Berger, Peter L. 1967. The Social Reality of Religion. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd.

- Botta, Marta. 2016. Neo-Collectivist Consciousness as a Driver of Transformative Sociocultural Change. Journal of Future Studies, Vol 21, No. 2, pp. 51-70.

- Braudillard, Jean. 2001. Seduction. CTheory Books.

- Campbell, Tom, Mark Davis, Jack Palmer. 2018. Hidden Paths in Zygmunt Bauman’s Sociology: Editorial Introduction. Theory, Culture & Society, Volume 0, No. 0, pp. 1-24.

- Cannon, Bob. 2016. Towards a Theory of Counter-Modernity: Rethinking Zygmunt Bauman’s Holocaust Writings. Critical Sociology, Vol 42, No 1: pp. 49-69.

- Evans, C. Stephen. 2004. Kierkegaard’s Ethic of Love: Divine Commands and Moral Obligations. Oxford University Press.

- Gane, Nicholas. 2001. Zygmunt Bauman: Liquid Modernity and Beyond. Acta Sociologica, Vol 44, N. 3: pp 267-275.

- Gary, Kevin. 2016. The Seduction of Kierkegaard’s Aesthetic Sphere. Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain, Annual Conference: New College, Oxford.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Polity Press.

- Golomb, Jacob. 1995. In Search of Authenticity: Kierkegaard to Camus. Routledge.

- Hardt, Michael. 1999. Affective Labor. Duke University Press: Boundary.

- Jakway, Chris L. 1998. A Kierkegaardian Understanding of Self and Society: An Existential Sociology. Dissertation: Western Michigan University.

- Jeffries, Vincent. 2005. Pitirim A. Sorokin’s Integralism and Public Sociology. The American Sociologist. Vol 36(3/4): 66-87.

- Kalberg, Stephen. 2001. The Modern World as a Monolithic Iron Cage? Utilizing Max Weber to Define the Internal Dynamics of the American Political Culture Today. Max Weber Studies, Vol 1, No. 2, pp. 178-195.

- Kettler, David. 1967. Sociology of Knowledge and Moral Philosophy: The Place of Traditional Problems in the Formation of Mannheim’s Thought. Academy of Political Science, Vol 82, No. 3, pp. 399-426.

- Kierkegaard, Soren. 1968 (1854-1855). Attack Upon “Christendom”. Princeton University Press.

- Kierkegaard, Soren. Trans. 1980 (1849). The Sickness unto Death. Princeton University Press.

- Kierkegaard, Soren. Trans. 2009 (1846). Concluding Unscientific Postscript. Cambridge University Press.

- Lazzarato, Maurizio. From Capital Labour to Capital Life. Ephemera Theory & Politics in Organization, Vol 4, No. 3, pp 187-208.

- Luttikhuis, Bart, and Moses, Dirk. 2012. Mass Violence and the End of the Dutch Colonial Empire in Indonesia. Journal of Genocide Research, Volume 14, No. 3-4, pp. 257-276.

- Mannheim, Karl. Trans. 1979 (1936). Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge. Routledge & Kegan Paul: London and Henley.

- Petersen, M, J. 2003. Genocide and Modernity. Copenhagen University: Centre for African Studies.

- Scaff, L, A. 1987. Fleeing the Iron Cage: Politics and Culture in the Thought of Max Weber. The American Political Science Review, Vol. 81, No. 3: 737-756.

- Sorokin, Pitirim. 1957. Social & Cultural Dynamics: A Study of change in Major Systems of Art, Truth, Ethics, Law and Social Relationships. Boston: Porter Sargent Publisher.

- Speier, Hans. 1985. Karl Mannheim’s “Ideology and Utopia”. State, Culture, and Society, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 183-197.

- Stewart, Jon. 2011. Kierkegaard’s Influence on Social-Political Thought Volume 14. Routledge.

- Stewart, Jon. 2015. A Companion to Kierkegaard. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Tiryakian, Edward A. 1965. Existential Phenomenology and the Sociological Tradition. American Sociological Review, Vol 30, No. 5, pp. 674-688.

- Weber, Max. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretative Sociology. Univesity of California Press.

- Weber, Max. 1992. The Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Westphal, Merold. 1996. Becoming a Self: A Reading of Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript. Purdue University Research Foundation.