A Kierkegaardian conceptual framework on society

Kierkegaard’s philosophical thought is strongly influenced by two streams of tradition: the intellectual tradition of Hegelianism during his particular period of time, and the religious tradition of Lutheran Pietism. The Hegelian dialectics is originally used to explain world history in a philosophical system. However, Kierkegaard have made strong critic towards Hegel in the Concluding Unscientific Postscript for its totalising philosophical system in viewing human history, and yet omitted philosophical reflection of the individual.

Kierkegaard’s critic on Hegel can be traced to his religious upbringing whereby Lutheran Pietism has stressed the importance of the individual. Pietism is a religious tradition that challenges the objectified theological system, de-objectifies the dogmatic structure and allows emotional internalisation of values into the subject (Berger, 1967: 59; Weber, 1930: 81). It may be stated that Pietism has placed the individual faith as the sole focus of religious life, and that though this method, one would experience transcendence and have a clearer view on the object of analysis. Although Kierkegaard does not completely deny traditional orthodoxy, his neo-orthodox hermeunitic has allowed the “personalising effect” in reading both religious and non-religious discourses.

As Kierkegaard attempts to reformulate his own dialectic to describe the individual’s phases of existential life, he combines both Pietism and Hegelianism. His Lutheran reading on Hegel found that the individual would pass through three existential stages: The Aesthete begins with the consumeristic and unexamined repetitive lifestyle, continues with The Ethical who abandoned his previous stage and began making choices and commitments which conforms to the ideal communal norms, and at the end, the individual, very rarely perhaps, would reach the religious stage whereby the individual by religious faith would transcend the ethical norms of his society and have a personal encounter with The Eternal Thou. In some sense, Kierkegaard reversed Comte’s three stages of society, from the positivistic into the religious, in clarifying the individual mode of living.

The epistemological structure of Kierkegaardian thought can be categorised into two distinctive types: it is knowledge about something or self-knowledge. Kierkegaardian philosophy points towards the relationship between the society and the self. However, his philosophical thought has once again placed greater emphasis towards the individual. It may be argued that knowledge about “something” comprises of objective scientific knowledge of society and individual. Knowledge of society is not only external, but it has relevance towards the individual in an existential manner: social context produces individual experience. It is by this ground that the connection between sociology and existential philosophy can be achieved (Jakway, 1998). At the same time, Jackway argued that Kierkegaard’s philosophical writing can be associated with symbolic interactionism and Marxism. The former emphasises the individual’s accumulation of social consciousness in the social context, the latter emphasises the ideological critique towards the society.

The significance of ideology critique is located in the birth of existential despair. As ideologies signifies the norms of society and its standard of successful living, therefore the same ideologies also signify the standard of failed living. In other words, every individual is experiencing daily anxiety that existentially threaten anyone who do not conform towards the communal norms of the crowd. Social meaning is derived from ideologies, or cultural mentality, as Sorokin suggested has impact towards individual personality (Jeffries, 2005). By describing the experience of such anxiety in individual, we are able to capture to what extend that certain ideology is or not authentic for the individual and social existence. Ideologies tend to over-idealise itself and thus it is crucial for one to be an “existential Marxist” to observe and avoid the potential decline society, being temporarily detracted from unauthentic crowd. However, unlike Marx who focused on the social-political group relation, Kierkegaard invites individuals to reflect the on psychological effect of modernity (Paula in Stewart, 2011: 37). Through the instrumental lense of negavity (via negativa), one is able to detect the limits of socio-political project and its decline (Golomb, 1991: 71). It is as Westphal argues that there are no political theory or any established order that is self-sufficient. (Tilley in Stewart, 2015: 485).

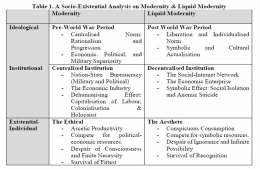

Sociologically, this conceptual framework is aimed to provide a general critique towards ideologies by relating it with individual existential experience. The method of criticising ideologies is not limited to the macro-abstract dimension, but it should be related into micro-existential level. The effect of ideologies produces differing existential states. In this case, modernity produces the Ethical individual, liquid modernity produces the Aesthete individual. Social context is parallel to individual experience. Just as how the historical transition from modernity to liquid modernity (Pre-World War to Post-World War period) depicts socio-cultural standards for successful living, individual experience would also show different existential properties and existential despair (Westphal, 1996: 20-34).

The relevance of structure & social changes to the individual

In the previous section, the author has described about the sociological framework of Kierkegaard’s philosophical themes. In this section, the author attempts to survey previous literatures on societal structure and social changes as the ground (social context) to support existential analysis of the individual. In this article, social structure can be differentiated into three major components: ideological, institutional, and individual. Sociological analysis is mainly focused on the macro (structural) and meso (institutional) level of analysis. The structural level of analysis is comprised of the societal values which regulates the society on the normative plane. The institutional level of analysis is supported by various social institutions which makes concrete of the societal values into everyday practices. On the individual level of analysis, it discusses the relevance of ideology and institution into individuals’ psychological-experiential condition, also known as the existential analysis.

There are several sociological writings which have tackled much on the issue of knowledge and ideology. The most prominent sociologist whom have attempted to systematise such analysis is Karl Mannheim. Mannheim differentiated knowledge and ideologies. Knowledge is the totality of ideas which organises a certain society in geographical place and historical time; knowledge can also be understood as the “social matrix” which overtly governs the structure of collective and individual. It is the “Social Soul” or culture of the society. In contrast, ideologies are the particular ideas which various socio-political institutions propagates to govern the population according to the interest of certain elite group. According to Mannheim, knowledge is neutral, but ideology is utopic in nature; just as how socialism is the ideological apparatus to promote communism – a classless society, ideology is the means towards the utopian end. The differentiation of knowledge and ideology is important because Mannheim argues that major amount of the population is not conscious towards the ideas which governs them. By tracing of the source of idea, as Mannheim stated, would provide a more comprehensive picture of the normative dimension, and that the individual or whoever so was observing the society, would not fall into the interest of certain ideological propaganda as proposed by political elites. The epistemology by which Mannheim applies in his sociological method is echoing Descartes’s view on the object-subject relation. The sociology of knowledge is about the knowledge which permeates in the society-individual relation, and the sociologist reads the society by making conscious of one’s independent ontological position with the society: by realising how one’s knowledge and behavior is molded from the after-effect of the societal normative source. The continual reflection of knowledge within oneself and the society, it is implied, that the observer (sociologist) is able to trace and map the ripples of ideologies in the institutional apparatus and daily social lives (Mannheim, 1979).

The second sociologist whom have discussed on the similar issue of knowledge is Pitirim Sorokin. Sorokin, unlike Mannheim, did not placed emphasis on the nature of ideologies. He utilises the term “cultural mentality” to describe the “social soul” of society. Sorokin argues that a certain society is governed by a logic-meaningful unity in the structure of norms. These meaningful “nodes of norms” are spread throughout the society in the culture, arts, science, and daily social lives, and when “dots are connected” they provide a general pattern which governs societal lives. Sorokin provided the example that Ascetism and idealistic philosophy is connected to one another, likewise Materialism and Empirical philosophy belongs to each other, as both types of notion share common metaphysical similarities in their respective areas. The former provides the ground for the ethic of absolute principles and the latter provides the social atmosphere for the ethic of happiness (Sorokin, 1957). Through three components of society (cultural, society, and personality), knowledge when it is made actual into the daily lives become an ethic – the collective individuals’ personality and individualised norms of living in the social environment (Jeffries, 2005). And yet, much about the argument which Sorokin proposed is different from Mannheim. Mannheim argues about how knowledge governs the social structure, Sorokin argues that knowledge (cultural mentality) is malleable, and the change of cultural mentality determines the properties of social structure and social lives. Sorokin described two different poles of living: the sensate which orients towards materialism and the ideational which orients towards idealism. Sorokin finds the “invisible hand” or Pendulum of Social change which directs social changes. When a certain society exhausted all of its previous resources to reach the peak of its culture, it encounters the moment of inertia and take a new form of cultural mentality, thus social changes happen.