What is the most apparent social change that we have encountered in the latest socio-historical period? The author would cite Bauman’s work that the most imminent and appealing changes is the shift from the knowledge and culture of modernity to liquid modernity in the 20th and 21st century. The pendulum shift is mainly driven by institutions which touches the fabric of social and economic lives. Modernity has been predominantly occupied by hard power resources such political-economic progress, and liquid modernity is filled with soft power resources like symbolic-consumeristic lifestyle. During the European Enlightment whereby the Western’s economic-political growth is dominated by industrial activities, the individual work ethic and cultural mentality supports the normative ideology of reason and progress. However, as it has been stated in the previous section that ideologies tend to exclusive in its own norms, European political and economic progress has at the same time allows the spread of Westerrn Imperalism, Colonialisation, the militarisation of nations, and produces the rational-bureaucratic form of Holocaust. The Western cultural mentality of reason has not only exhausted its scientific-economic resources but has abused its materials to produce tragic calamities in human history. In return, the traumatic response of Western society towards the tragic of World Wars has otherwise countered the ideology of immoral-reasoning progress and move towards the ideology of blissful possibilities. Liquid modernity, in this sense, allows the room whereby individuals could no longer fear the growth of economy into a weapon of war, but utilise capitalism for consumerism, into a lavish lifestyle. The sudden liquification of social structure has been the second most drastic change in Western history: the first liquification is against the authoritarian Church-State, the second liquification is against the militaristic national state (Bauman, 2005).

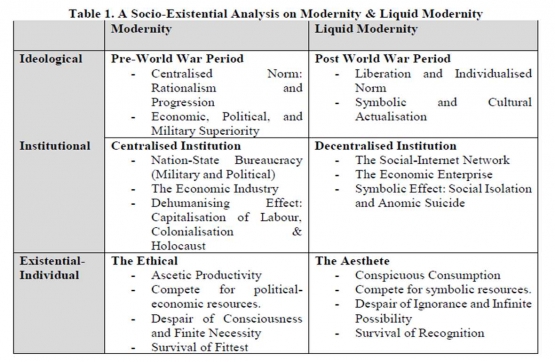

The position of Existential-Sociological analysis is to observe how does social structure (Ideology and Institution) and social changes (Modernity and Liquid Modernity) is affected into the individual’s existential mode of living. Every mode of living is derived from social context and individual’s choices, it is the I and Me in Mead’s terms. The constructed individual (me) takes his social energy from the ideological and institutional apparatus, and at the same time, the free individual (I) take the stance in the social environment. The stance of the individual is existential, and the author would like to use Kierkegaardian analysis to describe the individual’s existential relation towards the notion of modernity and liquid modernity. The following table attempts to provide a plotted summary on the relation between social context and the individual’s existential relation:

Modernity is understood as mode of social life which emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, it is highly engaged in the growth of science and industry. Giddens have stated that modernity is the historical discontinuity from the religious institution in Western Europe; the French Revolution is a particular socio-historical event which marked the new episode of epoch. Pioneering sociological thinkers such as Durkheim, Marx and Weber had observed that modernity is a “social metamorphosis” from the confined state of traditional socio-religious lives. Modernity is the fertile soil whereby the growth of capitalism and nation-state is also eventually realised (Giddens, 1990).

Modernity is a Western project of positivistic rationalism and socio-political progression in a linear historical grand narrative (Bauman & Bordoni, 2014: 122). The former is modernity’s counter reaction towards religious institution, the latter is the utopian project during the Enlightment. The sequence is introduced in August Comte’s stages of societal life beginning with the religious stage, philosophical, and then towards material-positivism – It is a critique towards the State-Church institution and a movement for objective reasoning and the construction of non-religious moralism. In this ideological scenario, religion has lost its former grip in determining individuals’ lives. The normative value by which modernity has constructed promotes efficiency for the cause of socio-political progression. If rationalism produces science and objective-positivistic paradigm, it also emerges in social forms through institutional apparatus.

Ideological umbrella is pillared by social institutions. Unlike other sociological thinkers, Weber predicted that the main cause of modernity and its dehumanising effect is located in bureaucracy; it is not about social solidarity nor class struggle as proposed by Durkheim and Marx. Bureaucracy is the institutional incarnation of rationalism, it is the catalyst which converts modern ideology into concrete everyday situation. Rationalism is not only defined within the scope of exact sciences whereby the philosophy of positivism is the most popular paradigm at that time, but it is the societal expression in the pursuit of fixed and objective value in human civilisation. As rationalism and science detracts the human dependency on the religious institution, bureaucracy shifted the dependency on the nation-state. The state purposes the legitimate power of the legal coercion to centralise and organise various industrial and socio-economic activities (Weber, ed. 1978: 165, 314). On certain degree, Weber saw that bureaucracy serves as a legal and effective means to organise economic labour to fuel industrial capitalism. He had also extended his arguments in The Protestant Ethic by claiming that Calvinistic ascetic values have similar logical-meaningful connections which stimulates capitalism in Western Europe. Religion, the old tradition of Europe although is vanishing, retains certain characteristics which enhances the new tradition of modernity. This argument might as well perhaps be Weber’s presupposition that modernity allows whatever kind of values to exist as long as it is adhering to the mentality of progression, whether it is scientific or religious.

Nevertheless, there are unintended consequences in modernity. Weber saw that the notion of “putting chaos into order” through the existence of bureaucracy has depersonalising effect that turns into social exclusion. If scientific inquiry reduced human beings into intelligent materials, the fatalistic commando of bureaucracy has reduced human individuals into industrial soldiers, or rather, machines. The extreme application of bureaucracy is known as “Iron Cage” whereby the citizens of labour movement is fitted wholly for economic-political purposes, thus reaffirming and reproducing the stiffness of the established order (Kalberg, 2001). And yet modernity’s “will-to-order” did not end as a mere solid modernity, it is extended to achieve “triumphant modernity”. Once again, as the ideological foundation of modernity also consists of socio-political progression, it is not only bureaucracy that became the industrial motor within the European civilisation, but it also involves Western Imperalism to extract industrial materials from outside the European geopolitical territory. As knowledge of “order and progress” are the ideological blueprints of

European tower of Babel, thus capitalism and colonialisation are twin coexisting materials which supported asymmetrical power relation of “the capitalist and labourers” in Europe, “the Occidental and Orientals” outside Europe (Campbell et al, 2018). Here, not only bureaucracy is used in the political sphere, but hard military power was assumed just means to achieve the ends of an “ideal” European civilisation. Weber who assumed that Calvinism is a rational-religious tool for capitalism, it is also the same idea that unknowingly justified colonialisation under the name of capitalism, modernity and religion: Gold, Glory, and Gospel (Luttikhuis & Moses, 2012). It appeared that modernity’s promise to liberate individuals to pursue objective-rational morality, has eventually been seduced by the objectifying power of Order and Progression. The extreme progression of economic and political affirmation, in the name of rationalism, has eventually abandoned ethical compassion, and revealed such dehumanising society such as the Holocaust and World Wars (Bauman, 1989: 15; Cannon, 2016; Petersen, 2003).

As we now transit to the Kierkegaardian analysis of the modern individual, I would like to propose the knowledge of modern society leans towards the ethical mode of existence. The knowledge of modern individual that he or she is living in a linear progress requires work ethic to pursue that aim. The Ethicist is one who is conscious of self and communal norms, striving to dutifully conform towards the ethical rules of the society (Evans, 2004: 47). The general pattern of individual living in the modern epoch is marked by ascetic living as it is claimed to be the most rational and effective basis for bureaucratic efficiency and industrial productivity. The individual who works ascetically is the ethical person, and one who is consumeristic is unethical, for the ideological notion of order and progress requires individual commitment towards the crowd. Without putting the individual into such existential position, it would be difficult to reinforce the Established Order of modern society. It does not mean that there is no single position for the Aesthetic individual (the consumeristic one), however, the ideal-type, knowledge, or cultural mentality of modern Europe is more logical-meaningfully sound to the Ethicist in Kierkegaard’s terms: one who is conscious that he/she is part of the communal project, and conformation to its ethical demands is necessary.

And yet, the presupposition that ethical commitment is mandatory also puts the modern individual into some form of despair. The first form is the despair of consciousness, which illustrates the individual as being alienated from the ideal self, is the existential struggle in seventeenth century Europe. If there is a grand-narrative progress, then one has yet to finish the long road, and it can be observed through social relations. The asymmetrical power relation that established social institutions places the individual in a continuum: one who ascetically conforms to the ideological-institutional criteria is the “the elite”; and “redundant people/wasted human” who fails to conform – both kinds of individuals in the modern game suffers the problem of comparison (Bauman, 2005: 95). The ethical state demands comparison of ethic that the individual who misbehaves is less ethical. And the presupposition that some individuals are “more ethical” (more conforming to Rational Productivity) is existing, the logical consequence of such arguments could also “rationally” claim that “the other” is justifiable to be excluded.

Furthermore, the ethical mode of existence in modernity is also susceptible towards the despair of lacking possibility and infinitude. The knowledge of modernity presupposes Rationalism and Economic-Political progression, and yet it also “post-supposes” the reduction of human individual into objects. As it has been mentioned that bureaucratic fatalism of Iron Cage has dehumanised individuals into mere bureaucratic-capitalistic compartments, and there are no other alternatives whereby individuals could “survive” if they leave the modern arena as “disqualified participants”. Thus, being reduced into industrial machine has become the “only” necessary path (despair of lacking possibility), and yet it is also a reductionistic approach which undermines human individual’s capacity for creativity and meaningful living (despair of lacking infinitude) (Kierkegaard, 1980: 33-42). At the end, the despair of the Enlightment is located in the notion that the materialistic and positivistic nature of modern knowledge is tuned to view human individuals as robotic machines of capitalism, colonialism and militarism.